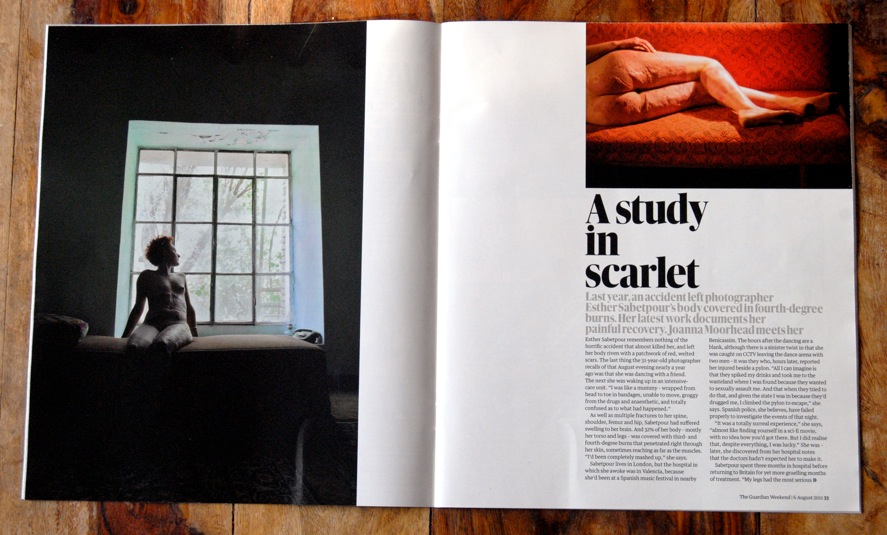

A study in scarlet: Esther Sabetpour - interview Last year, an accident left photographer Esther Sabetpour's body covered in fourth-degree burns. Her latest work documents her painful recovery. Joanna Moorhead meets her http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/aug/05/esther-sabetpour-interview-joanna-moorhead

Esther Sabetpour remembers nothing of the horrific accident that almost killed her, and left her body riven with a patchwork of red, welted scars. The last thing the 31-year-old photographer recalls of that August evening nearly a year ago was that she was dancing with a friend. The next she was waking up in an intensive-care unit. "I was like a mummy – wrapped from head to toe in bandages, unable to move, groggy from the drugs and anaesthetic, and totally confused as to what had happened." Sabetpour spent three months in hospital before returning to Britain for yet more grueling months of treatment. "My legs had the most serious burns, but to treat them they had to take skin from my torso, so that became badly scarred as well. For a long time the pain was all-consuming and I wasn't thinking about how I looked... but then the day came when I could look at myself properly in the mirror, around the time I returned to Britain. I was shocked by the severity of the scarring. The pain had been more than I could ever have imagined, but now it began to sink in how much my injuries had changed the way I looked as well – although I realised how lucky I was that my face and arms were pretty much unscathed." Just a few months before her ill-fated trip, Sabetpour – who juggles wedding photography with art projects – had begun work on a new set of images for an exhibition.

Her subject was herself: her naked body. "I'd always been interested in self-image," she says, "in ideas of identity and in the way women see their own bodies, and so often see the shortcomings rather than the beauty."

Now, she realised, her horrendous injuries meant she could explore these ideas in a whole new way. "This time, the body I'd be photographing would be scarred and red. Of course, back then, when I thought my body didn't look perfect, it absolutely was. Inevitably I look at those first pictures from before the accident and I think, 'What was I worrying about?' My body was beautiful." Sabetpour also used the shoots to play out the narrative of what happened. "It's very difficult to get over something when you have so many unanswered questions about what actually took place. I'm resigned to the fact that I may never know. But with my photographs I can play out the story. So in some of the images, for example, I'm lying on the ground and the picture is taken from above – and I'm in the position I would have been in when I was found at the foot of the pylon."

|

|

|---|---|

|

|---|